You’ve heard the stats.

All the way back in 1997 Nielsen showed that people don’t read online – they scan. And that’s only gotten worse. Today, you have about 8 seconds to capture a user’s attention on your website.

The human attention span is now shorter than that of a goldfish.

Despite this, many websites today fail to give users a single place to focus their attention when they first arrive. People land there and then they have no idea what to do next.

There are lots of buttons and lots of areas on the page… but they don’t have flow, and with social media, chat, and a cell phone never far away, that makes it highly likely that those shiny new visitors are going to wind up distracted and leave, never to return.

I firmly believe most sites start out in a good place. When someone decides initially to create a new website, they usually have a single idea.

Maybe they want people to sign up for their newsletter, or for a webinar.

And that’s great! It’s really simple. It’s clear. But then the main stakeholder has other ideas. Maybe they also want people to be able to find out more about the company’s products; or they want to give visitors a list of their best articles; or share their latest tweets… you get the idea.

Gradually, what was once a great idea for a site becomes the design from hell.

The idea behind the site isn’t bad. It’s that somewhere along the way, the stakeholder started to worry that not everyone would want to join their webinar.

So instead they try to put everything on the site. And put it all above the fold. Because it’s all important, right?

So, if we’ve known this doesn’t work since the 90’s why are we still doing it? And what should we do instead?

Why So Many Web Designs Go to Hell

The reason so many websites wind up in this downward spiral is because ranking priorities is hard. If you create a list of priorities and then try to label them a “1” (must have), a “2” (should have), or a “3” (nice to have), then it’s only a matter of time before someone decides something is even more important that the items labeled a “1” — and then before long, everything has become that important.

Raymond Chen, a long-time software developer at Microsoft (we’re talking since 1992) and blogger, calls this problem priority inflation.

- Priority 1: must have. If you don’t accomplish a priority 1 item, you may as well just cancel the project because it ain’t shipping.

- Priority 2: should have. If you don’t accomplish a priority 2 item, the product is significantly weaker, but you can still ship it.

- Priority 3: nice to have. If you don’t accomplish a priority 3 item, it’s not quite as awesome as it could have been, but it’s still a good product.

Over the past few years, I’ve seen a shift in the labeling of priorities in planning documents. A new priority has been introduced: Priority Zero. Nobody has explained to me what Priority 0 means, but I assume somebody invented it to emphasize that the feature is even more critical than priority 1. Mind you, I’m not sure what could be more important to a project than “If we don’t do this, we’re all fired.” Maybe “If we don’t do this, the earth will explode.”

As you might expect, priority inflation has a trickle-down effect. People whose features had been assigned priority 1 said, “Hey, how come my feature isn’t priority 0? It’s just as critical as that other guy’s feature.” Soon, everything that was priority 1 got reclassified as priority 0. Nature abhors a vacuum, so all the priority 2 items got reclassified as priority 1, and the priority 3 items got reclassified as priority 2.

The problem is that people are naturally bad at understanding what is actually urgent and what’s not. And when everything is important, none of them are.

At its core, everyone understands this problem. And yet almost everyone falls victim to it anyway.

How to Avoid the “Everything’s a Priority” Trap

This problem is so persistent that my team and I developed a system to help people create the information hierarchy of a landing page. We call it the “stair step model.”

Here’s how it works.

Start by identifying up to 5 things you want people to do on your page. The actual number of things you choose depends on how long you want the page to be. I generally recommend most people chose 3-4 tasks that people should do on that page.

Then you rank them from most important to least important.

When thinking about how to rank them, you shouldn’t just think about what’s most important to you; you should think about what’s most important to your visitor.

You may think the “most important thing” is that they buy a product, for example. But that probably doesn’t have a high chance of conversion — and is probably not the most important thing to the person reading the page. Instead, what they’re interested in is the solution they get from purchasing your product.

The second thing you want to consider is the difficulty in completing that action. If the most important action you want them to take (Priority Zero) takes 30 minutes to do, but your second most important task only takes 5 seconds, you might want to prioritize the second, as it has a higher chance of conversion.

Remember the formula: Desire / Time = Conversion

Now that you have your prioritization, let’s look at how to structure them into the page.

Step 1: The Hero Shot

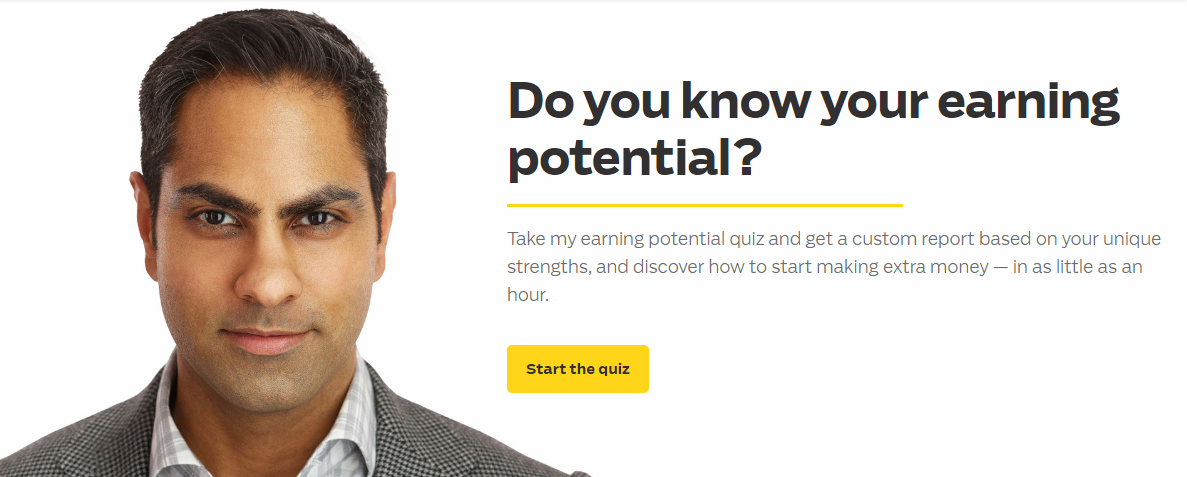

This most important thing becomes your hero shot. Generally, this is the top section of a website, where there’s a big picture of you and a big headline that talks directly to the pain point you’re going to solve.

(In my Japanese marketer days, we called this “Catch Copy,” because it catches the attention of the reader.)

For example, if we were building a page for a health and anxiety website, we might use the headline, “Stop being controlled by your anxiety and take back your life.”

Then, beneath that, there are a few smaller lines of copy that tell them what they can do (ex: We’ve built this assessment to help you determine whether you have anxiety). And finally, below the description is a big button that reads “Click here to take the assessment.”

This is our primary call to action. That means it should be something that someone who has never heard of us, has never visited our site, should be compelled to do based on just that headline copy and some small button copy.

This first section forms the first step of our staircase.

Step 2: Tell Me About Yourself

Below our first step is our second step (let me know if I’m going too fast there).

Anyone who hasn’t clicked on that first button obviously doesn’t trust us. Everything in marketing comes back to trust — an email is not just an email and a click is not just a click. It’s a transaction of trust and value.

So if someone scrolled past that first button then they’re not convinced yet that they should trust us. That means our next section needs to focus on building trust.

Maybe that means they need more tailored content. Maybe they need to understand the results of other people, and we can provide testimonials. Maybe they need social proof, and we can share social proof icons.

Let’s say we go with that third option, so after the first section we have a section with the logos of publications where we’ve been featured. We say we were in the New York Times; we were featured on ABC; we’ve been interviewed by NPR.

We add a bit of copy that shares that we do, what we’re really good at, and asks the visitor to tell us what they’re looking for.

There was something there that was almost blink and you’ll miss it: “Tell us what they’re looking for.” This is a chance to let your visitors self-select into the content that will most likely turn them into leads, and customers.

This self-selection has two powerful points.

- The visitor is getting content that applies directly to their issue, which is much more valuable than generic content.

- By looking at our site analytics, we can tell which of the pain points most of our visitors are experiencing. Once they opt in, we can also determine which pain points are the most effective at converting from leads to customers.

This becomes our second call to action.

If they click on it great! If not, then on to stair step three.

Step 3: Share a Story

At this point they’ve missed two calls to action. That means we need to find a way to empower them a bit more. We need to take a softer approach.

This is where we might add in a personal story, sharing the problem we had that we overcame that led us to create our product or business. Or maybe we share a client’s story or testimonial.

This time we don’t ask them to do something right now — instead, we use a button that says something like, “Learn more” or “Find out how…”

We’re inviting them to have a larger conversation; this is good for people who are looking around and trying to figure out what it is they want. They’ve passed the direct “Do this now” and the “Tell me about yourself” steps. That likely means this person is someone looking for a solution, but who isn’t really sure what that solution should be yet.

Step 4: The Final Step

If they pass step three and are still scrolling then I generally think this person isn’t actually looking for a solution — they’re just gathering information. So that’s where I like to include information about you or the business, or a block with a few of your most popular blog posts.

The call to action for that section becomes, “Check out these articles” or “Don’t know where to start? Start here.” And that becomes your fourth and final step.

With the Stair Step Model You Build a Better Website

Using the Stair Step method allows you to avoid the usual problem of “everything is important” by creating a prioritized and logical order for your users to follow down the page.

It allows you to capitalize on different user types without cannibalizing your design. That is, it allows you to build a better website — one that lets you return to the good place you started from.

What’s your top priority — the one action you want users to take — on your website? Share it in the comments.